I walked into the Chiang Mai Art and Cultural Museum and immediately encountered a small theatre, where a time lapse ode to Chiang Mai played in a loop on a screen. Images of Chiang Mai’s mountains, temples, monks, food vendors and dance performances flitted by, vibrant images of what makes Chiang Mai, Chiang Mai. As I wandered into the next room, I saw prehistoric Chiang Mai, and was soon swept on a journey through 700 years of the city’s history. Within each temple, small village in the mountains, and street market vendor, I learned, there was a story, and history.

Museums are, at their core, historical oases. They present us with our past. Yet, people often feel removed from the past they’re viewing. The glass cases can give one the impression of a zoo, in which the materials on display are to be stared at, rather than interacted with. One may walk through an exhibit passively, with the information simply washing over the onlooker. However, museums should not be viewed passively, they require interest and interaction. If we don’t take the time to draw connections between a museum and the culture and people it represents, we lose a valuable opportunity for growth.

“It’s easy to make a museum just a museum. People come, I sell a ticket, it’s easy to say it’s beautiful, it’s done. It’s not easy to have people come, to talk to them every year, every day,” said Suwaree Wongkongkaew, Director of the Chiang Mai City Arts and Culture Centre (CMCACC). Suwaree hopes that museum-goers will take advantage of the unique access that the CMCACC, and museums like it, give to the cities they represent. Her goal for tourists is to help them better understand the city through the eyes of its people and stories of its streets. Suwaree explained, “I want visitors to get a snapshot of time so when they leave the museum to explore the city, they can understand Chiang Mai [and its values] better…Visitors must understand the significance of a wat, the strategy of a city’s layout, and, most importantly, how they should conduct themselves within a city, and the local people.”

Suwaree was recently on a panel discussing “Community Engagement in Museums” alongside Dr. Joanne Hyppolite’s, the curator of the Smithsonian National African-American Museum of History and Culture in Washington D.C. During the panel discussion, Dr. Hyppolite talked about how community engagement is integral to her museum’s existence. She emphasised that as her team put the museum together it was their priority “not to tell the community what their history was.” Instead, Dr. Hyppolite let the community determine what story was told. She collected hundreds of old photographs from family archives and spoke with countless members of communities from different regions around the United States regarding what to exhibit in the museum. Finally, in one part of the museum, Dr. Hyppolite included recording booths for visitors to record their own stories and histories to be featured in a later exhibition. As a result, the museum is not simply a collection of impersonal artefacts, it’s an accumulation of lived experiences. Thus, the walk through the museum is not a passive one, it’s a walk filled with countless conversations with the past and the people who were a part of it.

Suwaree is attempting to accomplish a similar feat at the Chiang Mai City Arts & Cultural Centre. “I don’t only want to explain history,” she said, “but have the participation of the local community as well.” Suwaree has been working with five NGOs to better engage the local community and has generated a new project titled ‚Revitalise the Old City‘. Through the project, Suwaree and her team mapped out the 13 communities in Chiang Mai to collect information for the museum. In her efforts to empower individuals from these communities to preserve their cultures, she has also invited them to interact with the CMCACC collections and use their facilities to hold meetings. The project has been running for more than three years, and has served as a means to bring locals closer to their roots and generate conversation.

She went on to explain how strengthening these ties to communities’ cultural roots is not only crucial from a preservation standpoint; future generations have a responsibility to understand their ancestry and culture. ‘Revitalise the Old City‘ poses an opportunity for youth in these communities to forge such connections with their heritage. In this way, CMCACC and museums like it facilitate interactions between the past and present, for locals and tourists alike. “Everyone has a responsibility to understand the values of the city, deep in their heart,” she said. “Any one of the 30,000 children currently growing up in Chiang Mai could become a leader in their community, and they should feel a need to uphold these values and protect the city.”

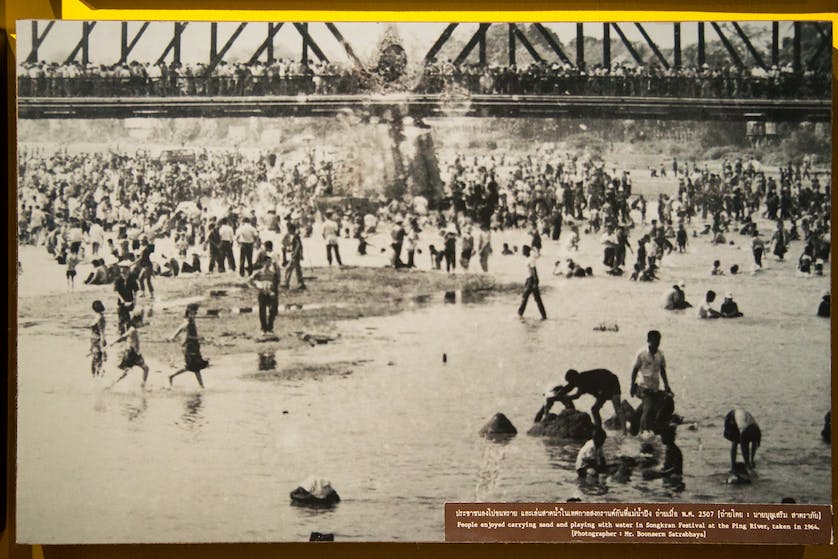

The day after the panel, I went to The Chiang Mai House of Photography to see the current exhibition: “Photographers and Photographs of Chiang Mai’s Past No. 1”. The exhibit featured snapshots from around Chiang Mai, many of which included locals interacting with some of Chiang Mai’s iconic structures and locales. I paused in front of a photo of children laughing and playing in water during a Songkran celebration years ago near the Iron Bridge, before the construction of the Mae Ngat Dam in 1985. A museum guide explained that locals would celebrate the New Year by heading down to the river, as pre-dam unmanaged water levels were at their lowest in April. “People would sell food, hangout, and play. It was important to the locals,” she noted. “But a dam was constructed to ensure water flows all year long, and those celebrations are no longer possible.” Looking at the photo, I recognised that I had been at the Iron Bridge just the night before. I had crossed the bridge completely unaware of the stories embedded in and below its iron rods.

Standing in front of the photo, it occurred to me that the way I first experienced the bridge is the way most people probably experience the city: mindlessly, without the aid of historical context. The memories of Chiang Mai are often trapped in pictures in museums people don’t go to, or only kept alive in the hearts of those who have experienced them. This is what Suwaree is combating through her initiatives to enhance museum engagement.

Along with her projects at CMCACC, Suwaree is also leading the push, as Chief of City Development, to categorise Chiang Mai as a UNESCO world heritage site. Typically, UNESCO ‘world heritage site‘ status is given to single monuments or historical parks; giving this title to an entire city, would make the city itself an exhibit. While the city of Chiang Mai wouldn’t technically adhere to the traditional definition of a museum laid out by the International Council of Museums, being a world heritage site would posit it as a living, breathing museum.

“Our city is our museum,” Suwaree Wongkongkaew stated. It remains to be seen whether UNESCO will agree to the proposal, but Surawee’s efforts serve as a good reminder of the true purpose of museums. A visit to a museum is filled with opportunities for cultural immersion. It should not be like going to the zoo, it should be like entering a jungle. Whether it’s through the music and dance of a hill tribe, the photographs of a revolution, or the words of a child, museums make it possible for us to take in cultures as a sensory experience, all under a single roof. They are places where we can equip ourselves with the information we need to interact with our surroundings in a meaningful way.

The purpose of museums extends beyond the mere notion of preservation. They have the potential to provide their guests with an enhanced lens for the present. One should interact and learn from the information presented; one should not simply stare at the objects on display through the glass.